I’m keeping this one brief, as I’ve had my head down working on a new WIP lately and haven’t been watching the current events in author-space as much as I normally would.

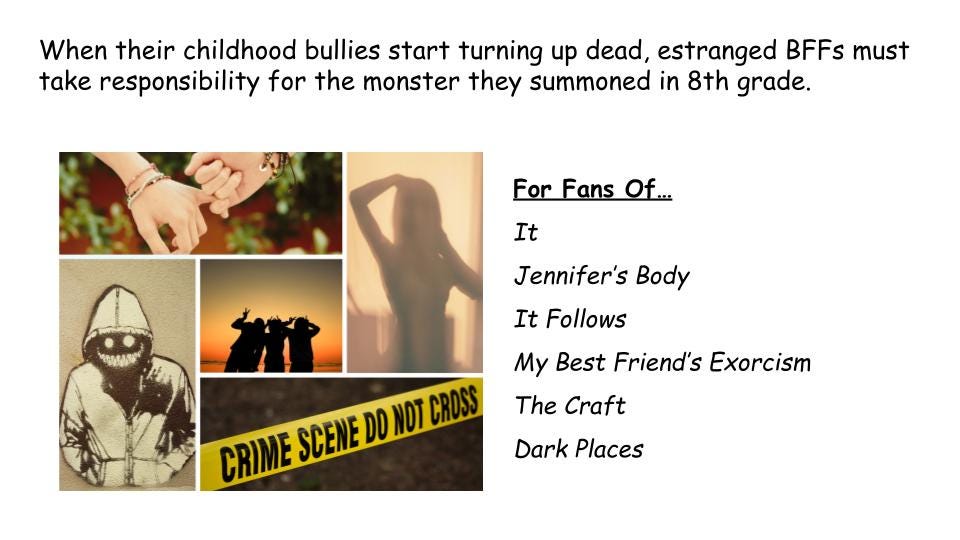

The new WIP is going to premiere on Wattpad next month with a little sample teaser, and we’ll see where it goes from there. It’s been a while since I’ve produced some Wattpad content and this particular story I think is primed to do well there. Here’s an obscure little teaser to get you intrigued:

I’ll be sure to link it when it goes live so you can see it well before it might ever be posted anywhere else :)

And now, with that out of the way…onto this month’s deep dive.

The hot-button news item this year, at least among creatives, has been artificial intelligence. Generative AI went from a fun novelty in late 2022 to a looming existential threat to writers, musicians, artists, actors, filmmakers, and anybody else who creates anything. With a touch of a button or a few keystrokes, anybody can make anything, and we're all out of a job. Right?

Well, not exactly. Tools like ChatGPT and Midjourney have ample limitations that become apparent once you start scratching below the shiny surface. They are very impressive until you actually start trying to use them for anything of substance and realize how flimsy their outputs are. But that doesn't mean every CEO and art director sees it that way, and even if they haven't fired their creative teams just yet, the implications of generative AI are exhilarating and disturbing in equal measure.

But here's the thing. This is far from the first time we've felt threatened by artificial intelligence. And as it turns out, our anxieties about the robot uprising cut a lot deeper, and go back a lot further, than you may expect...

The word "robot" was coined by Czech playwright and intellectual Karel Čapek in 1921, in his play R.U.R. -- usually subtitled in English as "Rossum's Universal Robots." Although the word rapidly escaped to join the modern English lexicon, few people today seem to mention R.U.R. or even acknowledge its existence...which is a real pity, as it tells a disturbingly prescient tale and deserves credit for singlehandedly inventing the genre of robot rebellion sci-fi.

An English translation of the script is available on Project Gutenberg, for the curious.

Primarily set in the fantastical futuristic year of 2000, the play is a tragedy in three acts. It begins when Mr. Rossum (whose name roughly translates to "Intellectual") discovers a miracle substance that allows him to create life. He uses it to manufacture humanoids called roboti. And though Rossum himself is satisfied simply with this discovery for its own sake, it's quickly seized upon and commercialized by his nephew, who has dollar signs flashing in his eyes.

(Roboti, for the record, is a play on the Czech word "robota," which means "serf" or "worker" or "slave laborer," depending who you ask. Apparently Čapek nearly named them "labori" first, before his brother Josef, a cubist painter who would later die in a Nazi concentration camp, convinced him to change it.)

Anyway - flash forward in the story and soon these roboti are being mass-produced and used as laborers. A sympathetic woman named Helena endeavors to put a stop to their mistreatment and secure them equal rights. But, freed of their restraints, the roboti don't want to be equal; they want to take over. So they rise up to wipe out mankind, only to discover once they've succeeded that they cannot reproduce without human assistance. The story ends with a surviving pair who have seemingly transcended the boundaries of humanity and may become the Adam and Eve of the new world....or maybe not. Perhaps it's all hopeless. Curtains fall.

The BBC filmed a television broadcast of the play in 1938, although the footage has been lost to history. Only a few photos remain. There's a new film adaptation currently in pre-production, though, directed by Alex Proyas (otherwise known for I, Robot and The Crow among other things) so keep an eye out for that one.

On the Humanity of Robots...

There are several fascinating layers to Čapek's story. Writing as he was in the wake of WWI and its rampant technological advancements -- many of them horrifying, some quite wonderful -- it's not hard to see some anxieties about the growing power of manufacturing in his work. And R.U.R. is, of course, a tale of hubris. It's a story about a man who attempts to replace god, who creates a race of beings who themselves end up destroying their creator -- it's not exactly a subtle warning.

And that story, the one of man's hubris, is one we've seen time and time again. It echoes Frankenstein of course, but warnings against hubris are at least as old as that word, taking us back several thousand years to Ancient Greece and the roots of Western Civilization. And obviously, I would be remiss not to point out the similarities to the Jewish Golem, a constructed fantastical being created to serve a master and prone to running amok.

But I'm less interested in those threads than in the implications of the rebellion. Because the story I outlined above is such a common framework, such an archetypical plot, that I hardly needed to recap it; when you hear about a robot uprising, that's the exact story you imagine. But why?

Because here's the thing about Rossum, and about robot uprising stories in general: They're not so much realistic reflections of the true threat of artificial intelligence, as they are a reflection of our exploited underclass. Remember, dystopian fiction doesn't tell the future, it holds a mirror up to the present.

I find it fascinating that the work that introduces the very concept of robots, also introduces the idea of the robot rebellion, as if the two thoughts are completely, inextricably linked. That if we were to create a race of humanoids, that they would by their very nature be compelled to destroy us. After all, we'd create them in our own image, and what is the human legacy if not one of revolution, conquest, and hostile takeovers?

The Conqueror's Anxiety

That's the fear at the heart of replacement theory, right? The reason why some people become so uneasy about immigrants is a a worry that they'll come to this country, overwhelm the existing population, and overwrite its culture with their own.

Because that's what colonizers do. And, surely, every group secretly desires to colonize and subdue others if given half a chance, right?

The inherent anxiety of the colonizer (or the slave-master, for that matter) is that your position at the top of the heap is precarious. When you know that you (or your forebears) is in power thanks to the violent subjugation of others, it's not too hard to imagine you're next on the chopping block for future violent subjugation.

But historically, that...doesn't seem all that common, in reality. History's most famous slave rebellions mostly ended in tragedy for the rebels. Even in instances where an enslaved group managed to escape capture and gain independence, we don't tend to see them drunk on newfound power, spreading beyond their borders to go colonize some other place.

As it turns out, generations of oppression and enforced poverty don't really leave disenfranchised groups with the necessary resources to become major world powers. Who'd've thought?

I'm sure that someone with a greater knowledge of history than me could find me some counter-examples, but I spent some time wracking my brain trying to think of an example of a disenfranchised group that went on to overthrow their bonds and become a colonizer, and those examples are pretty few and far between. Certainly nothing that follows that neat, clean progression we're so accustomed to seeing in storytelling, where the oppressed so often becomes the oppressor (usually in service to a certain "there's very fine people on both sides" flavor of upholding the status quo).

Arguably the greatest success stories of oppressed-becomes-oppressor are the Christians, though their history of religious persecution may be...somewhat overstated. It's complicated. That deserves a whole essay of its own, frankly, because we don't have time to unpack all of that right now. Let's get back to the robots.

A Brief History of Robot Rebellion in Film

Aside from R.U.R., there are plenty of landmark films documenting the rise of the machines, in various incarnations. The earliest of these may be Fritz Lang's 1927 classic fever dream Metropolis, which paints a futuristic vision of a corporate hellscape all-too-familiar to us now. A robot built as a replacement for a dead woman instead takes it upon herself to dismantle the titular metropolis by way of fomenting rebellion (among other things).

In the 1950s, Isaac Asimov conceived of the Three Laws of Robotics, a set of rules governing how robots might peacefully coexist with humans...and then immediately began to explore what would happen when those rules go awry. His short stories in I, Robot treat the matter with a bit more subtlety and depth than the 2004 Will Smith film, but hey, to each their own.

By 1968, Stanley Kubrick and Arthur C. Clarke teamed up to create 2001: A Space Odyssey, which takes an elliptical journey through human history but ultimately circles around HAL 9000, a computer who resorts to murder to prevent any interference with the orders it was given.

In 1982, there was Bladerunner, based on the 1968 Philip K. Dick book Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep. Both are about androids known as replicants who are trying to live their best lives, but which pose an apparent threat to humans on account of being fundamentally better at everything.

Two years later, of course, there was Terminator, which is probably the #1 thing you think of when you hear about the robot uprising. Here, a neural network called Skynet is waging such a vicious battle with humanity that it resorts to both time travel and nuclear holocaust. Why would it do such a thing? Because it understood that humans wanted to shut it down...and it didn't want to die. How very human!

Of course, there's also The Matrix trilogy, where it's revealed that not only is reality as we know it a simulation, its purpose is to keep humans docile so they can act as a power supply for the machines that now run the world.

There are other tales of robots taking over the world (or simply going rogue and hurting people, as in M3GAN). The robots themselves are not always an exploited underclass of workers who throw off the shackles to take over. Sometimes they're merely there to hold a mirror to the humans they encounter by asking the existential question, "What does it mean to be human?" And sometimes they're there to show that, even if machines are smarter and faster and better, that humanity is unique and special enough to persevere.

But whatever they're doing, the #1 thing robots do in fiction is tell stories about people.

The Clear and Present Danger of Artificial Intelligence

I would posit that the workers of today have a whole lot more in common with the robots in fiction than with the human victims of the rebellion. If we are replaced by machines, it won't be because those machines got tired of being treated like slaves and decided to give us uppity humans a taste of our own medicine. It will be because the cancerous machinery of capitalism will find more profit in automation than a workforce of humans with their inconvenient needs and desires and dreams for a better world.

And maybe that's why we love these robot rebellion stories so much. Because we see ourselves in both slave and master, human and machine. For a couple of hours, we can indulge in both the power fantasy of rebellion and the comforting fiction of human superiority, even as we exorcise our anxieties about the economy and forward march of technology and the realization that none of us have any real power in this world, not really.

As we sit in the dark theatre, surrounded by the warmth and breath of fellow humans, no one needs to know whether we're secretly rooting for the machines.